Deep beneath Guangdong’s granite hills, a groundbreaking experiment has officially started. The Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory, or JUNO, began collecting data on August 26, 2025, following more than a decade of planning and construction.

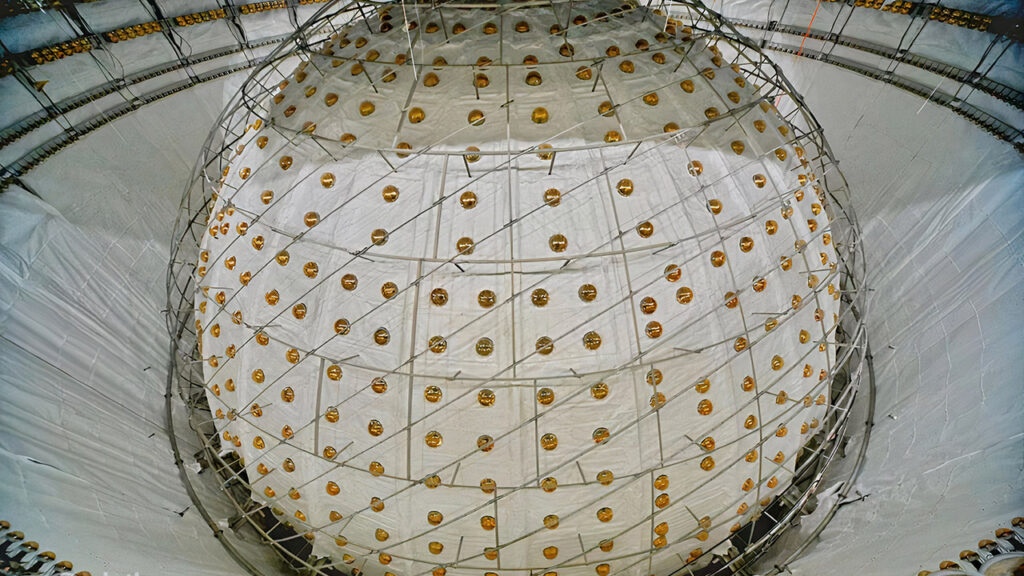

JUNO sits 700 meters underground to shield it from cosmic radiation, with its core being a 35.4-meter-diameter acrylic sphere holding 20,000 tons of linear alkyl benzene, a specialized liquid. When a neutrino—particularly antineutrinos from nearby nuclear reactors—interacts with this liquid, it emits a faint blue flash. Surrounding the sphere are 43,200 photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), each with highly sensitive detectors that capture these flashes and convert them into electrical signals for scientists to analyze. The sphere floats inside a 44-meter-deep pool of ultra-pure water, monitored by 2,400 extra PMTs that filter out cosmic muons. JUNO is 20 times larger than any previous detector of its type.

Neutrinos are nearly massless, electrically neutral, and can pass through matter almost unhindered. Yet they hold clues that could transform our understanding of physics. JUNO’s primary goal is to determine whether the third neutrino type, v₃, is heavier than the second, ν₂. This isn’t just theoretical; the answer could illuminate why matter dominates antimatter and reveal processes behind star and galaxy formation. By measuring antineutrinos from the Taishan and Yangjiang nuclear power plants, 53 km away, JUNO detects roughly 45 interactions per day, gradually building an energy spectrum that uncovers the neutrino mass hierarchy.

Unlike previous experiments, JUNO’s measurements are unaffected by Earth’s matter or tangled in complicated parameter correlations. Its energy resolution is unmatched, thanks to the acrylic sphere’s transparency and the PMTs’ sensitivity. Smaller 3-inch tubes fill gaps between the larger 20-inch PMTs for maximum coverage. Early commissioning runs, including a reactor neutrino event on August 24, 2025 with energies of 5.7 MeV and 2.2 MeV, already indicate the detector is exceeding expectations. Its precision could reduce neutrino oscillation parameter uncertainty to 1%, a significant improvement over Daya Bay’s 4–7%.

Beyond its core mission, JUNO will monitor solar neutrinos for real-time insights into solar activity, detect signals from distant supernovae, study geoneutrinos from Earth’s radioactive decay to understand mantle dynamics, and search for sterile neutrinos or proton decay. With a projected lifespan of 30 years, JUNO can later be upgraded to hunt for neutrinoless double-beta decay, which would determine if neutrinos are their own antiparticles—a discovery that would rewrite particle physics.

The $376 million project involves more than 700 researchers from 74 universities across 17 countries, including the University of California, Irvine; the Technical University of Munich; and institutions in France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Taiwan. China provides over 80% of the funding, drawing heavily on experience from the Daya Bay experiment (2011–2020), which made a landmark neutrino oscillation discovery. UC Irvine is the sole US university fully participating, contributing to design, assembly, and data processing, with support from the National Science Foundation.

Constructing JUNO was a formidable challenge. The acrylic sphere, weighing over 600 tons with 120 mm thick walls, is the largest of its kind. Filling it with 20,000 tons of liquid scintillator and displacing 60,000 tons of water demanded centimeter-level precision to avoid structural failure. Every element—from the purity of the liquid to PMT calibration—had to meet exacting standards. “It required not only new technology and ideas but also years of careful planning, testing, and patience,” said JUNO’s chief engineer, Ma Xiaoyan.